CONCILIATION OF

THE PAST, PRESENT,

AND FUTURE

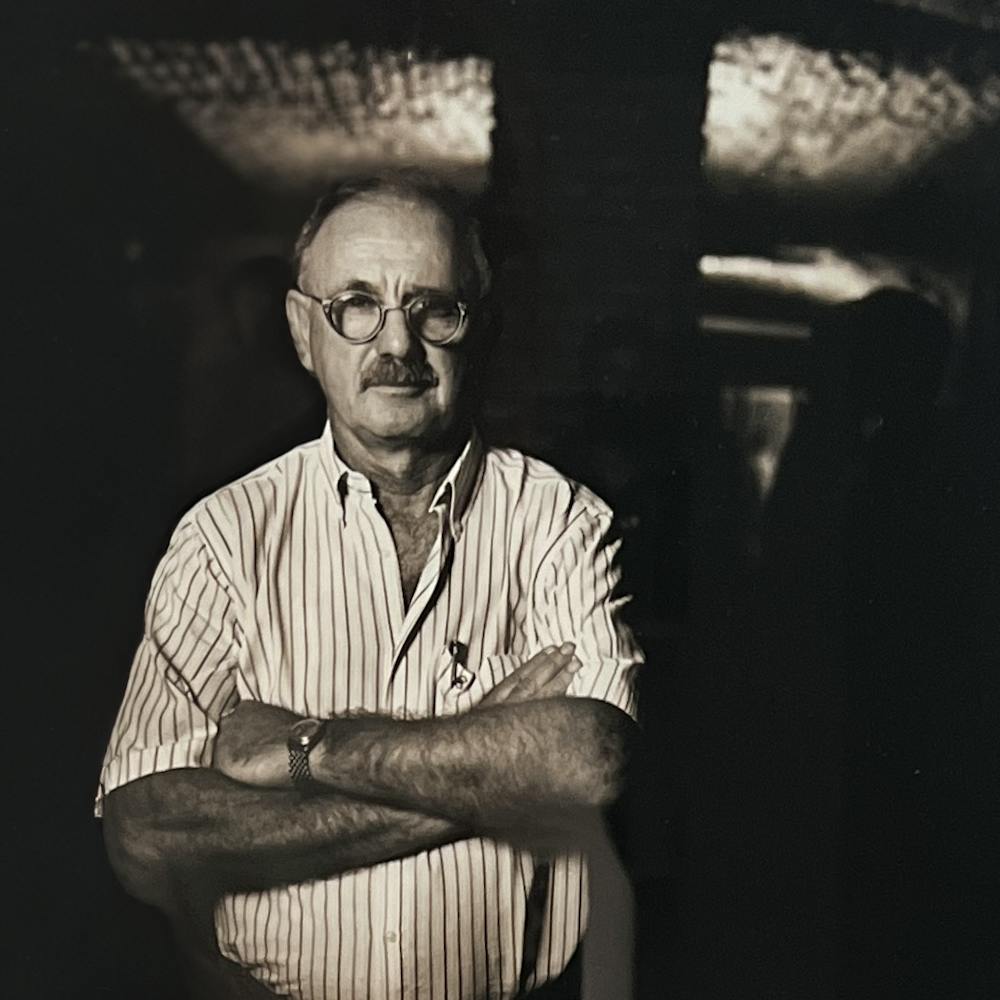

For 38 years, founder Jorge Eckstein’s life was consumed by excavating and preserving El Zanjón’s long-forgotten underground tunnels and restoring the landmark buildings above. With unwavering dedication, he has woven modern ideology into the mysteries of the past history, revealing the essence of Buenos Aires through architecture, history and literature.

1536-1778

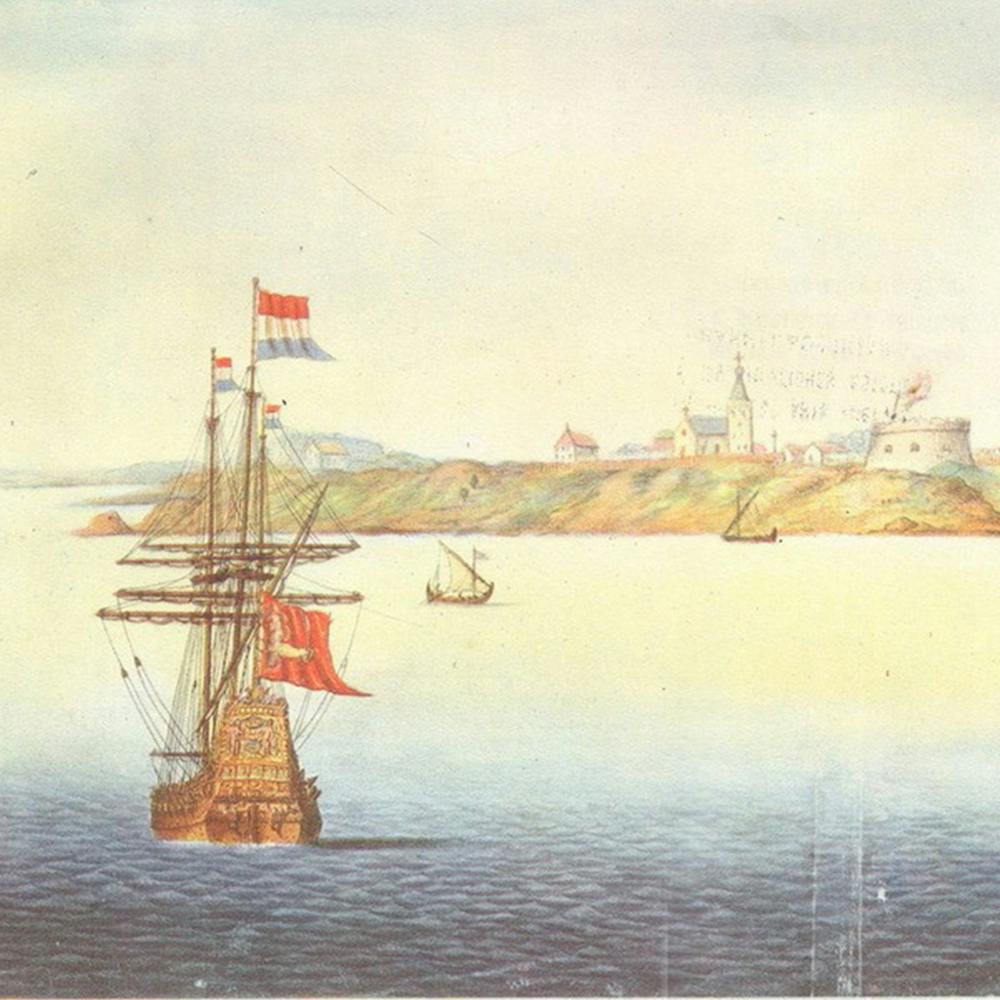

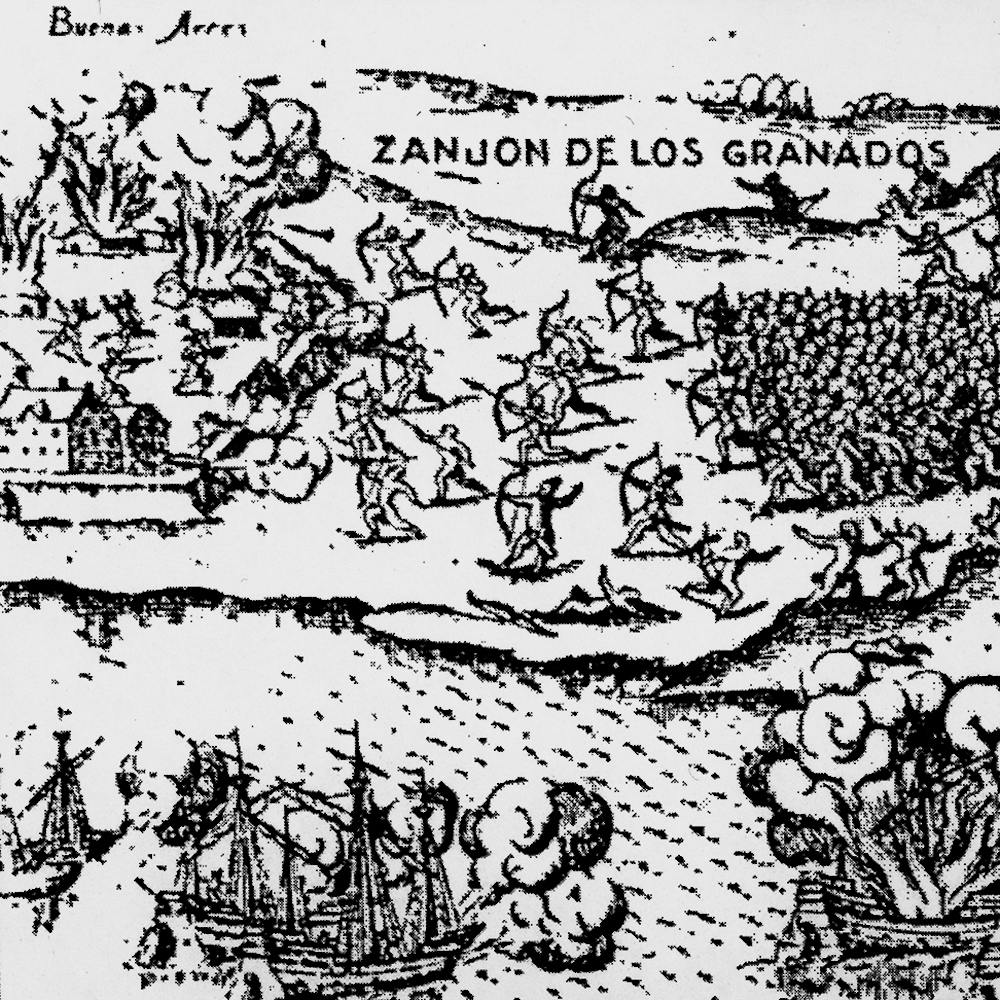

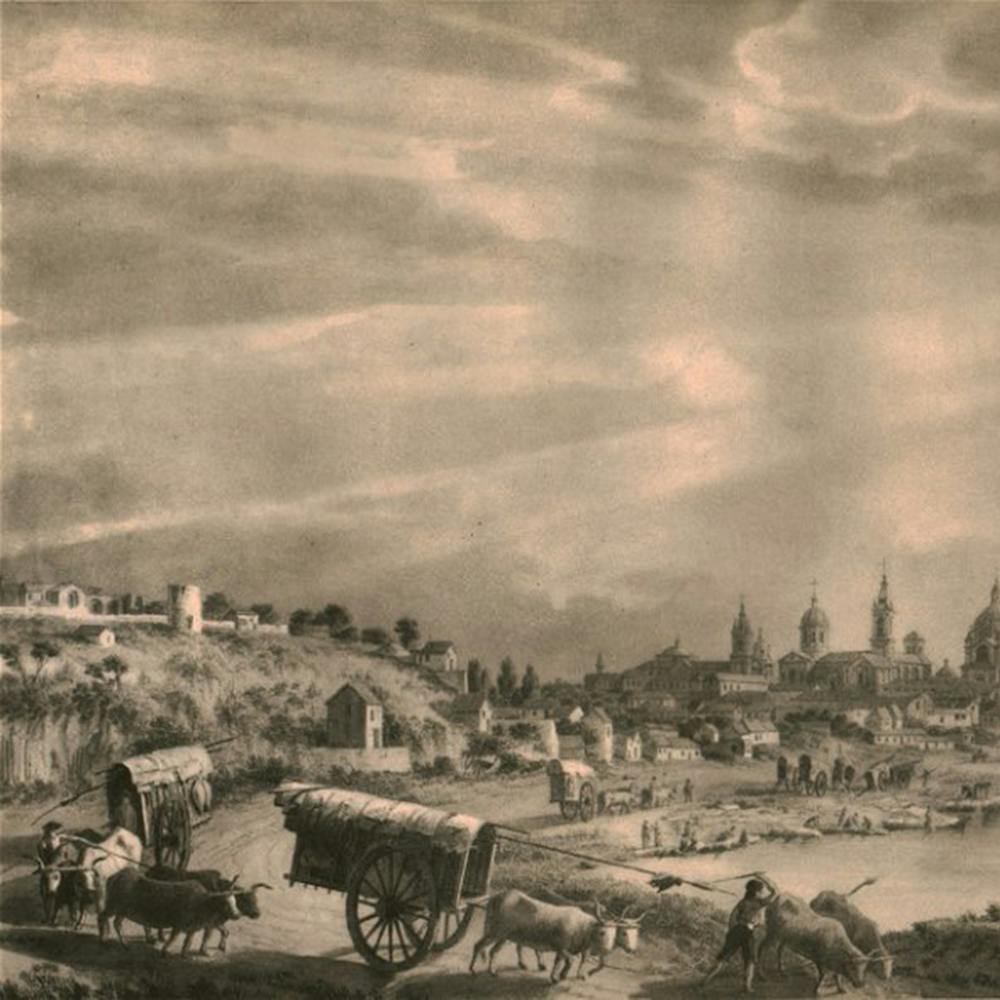

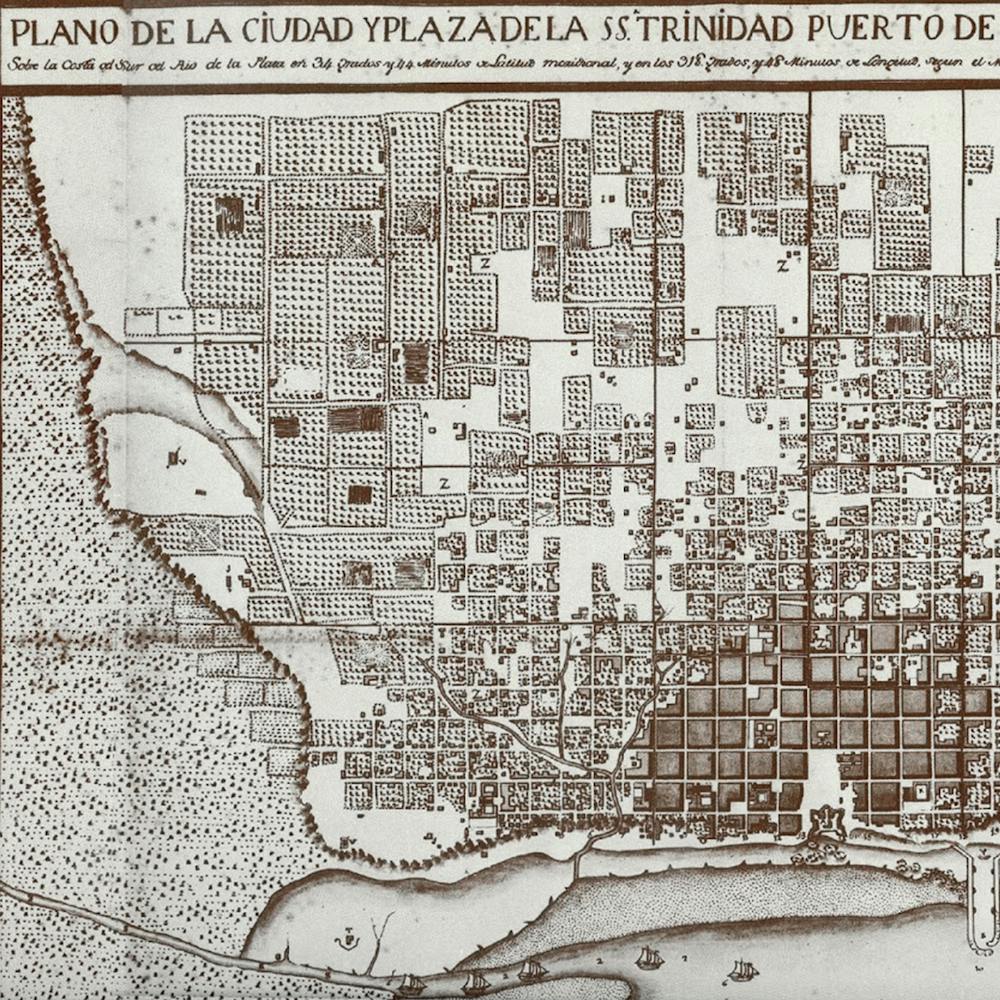

When the Spanish colonizers arrived, they chose the area surrounding El Zanjón to build their first settlement. During the rainy season, rainwater would drain from the heights into the River Plate through three ravines that the Spanish called Los Terceros (The Thirds), flooding homes and forcing residents to stay indoors for days. The southern Third crossed the land where El Zanjón is located today and runs under the Los Patios and El Puente buildings.

1536

Spanish explorer Pedro de Mendoza marks the first settlement of Buenos Aires.

1580

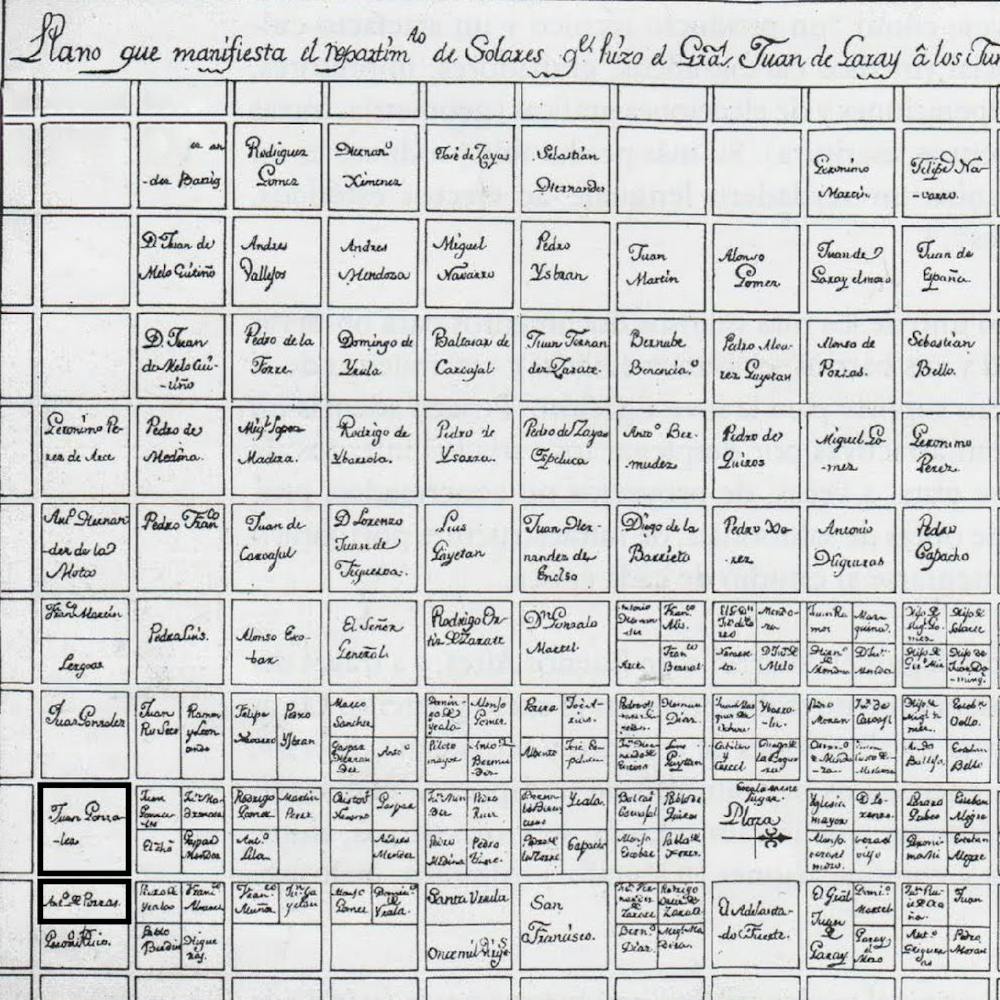

In the second attempt at founding Buenos Aires, Juan de Garay successfully established the city's southern border at the El Zanjón de Granados ravines.

1583

Juan de Garay gave large pieces of land in Buenos Aires to members of his expedition. The area where El Zanjón sits today was gifted to Juan Gonzalez.

1689

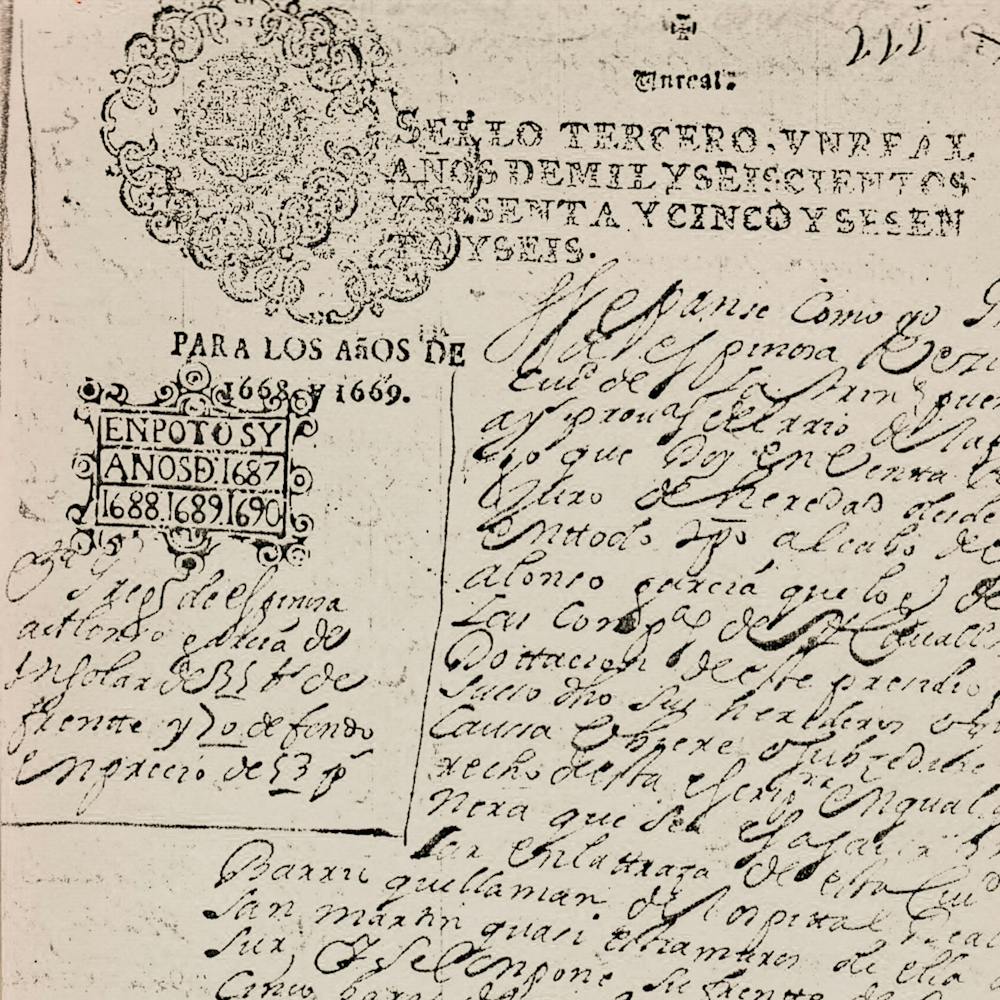

The first sale of Los Patios, which now has a small house on the lot, is registered by Gregorio Diaz de Espinosa, the grandson of Juan Gonzalez.

1779–1910

In 1767, Marcos Miguens travelled from Galicia, Spain to Buenos Aires. A notable citizen, Miguens carried out high-profile civil work, alternately taking over the responsibilities of the justice of the peace, the commissioner and the Mayor of the Holy Brotherhood. By 1830, the Miguens family had purchased an additional 200,000 acres of public land, making them one of the largest landowners in the Pampas.

1779

Marcos Miguens purchases the Los Patios land with a small house.

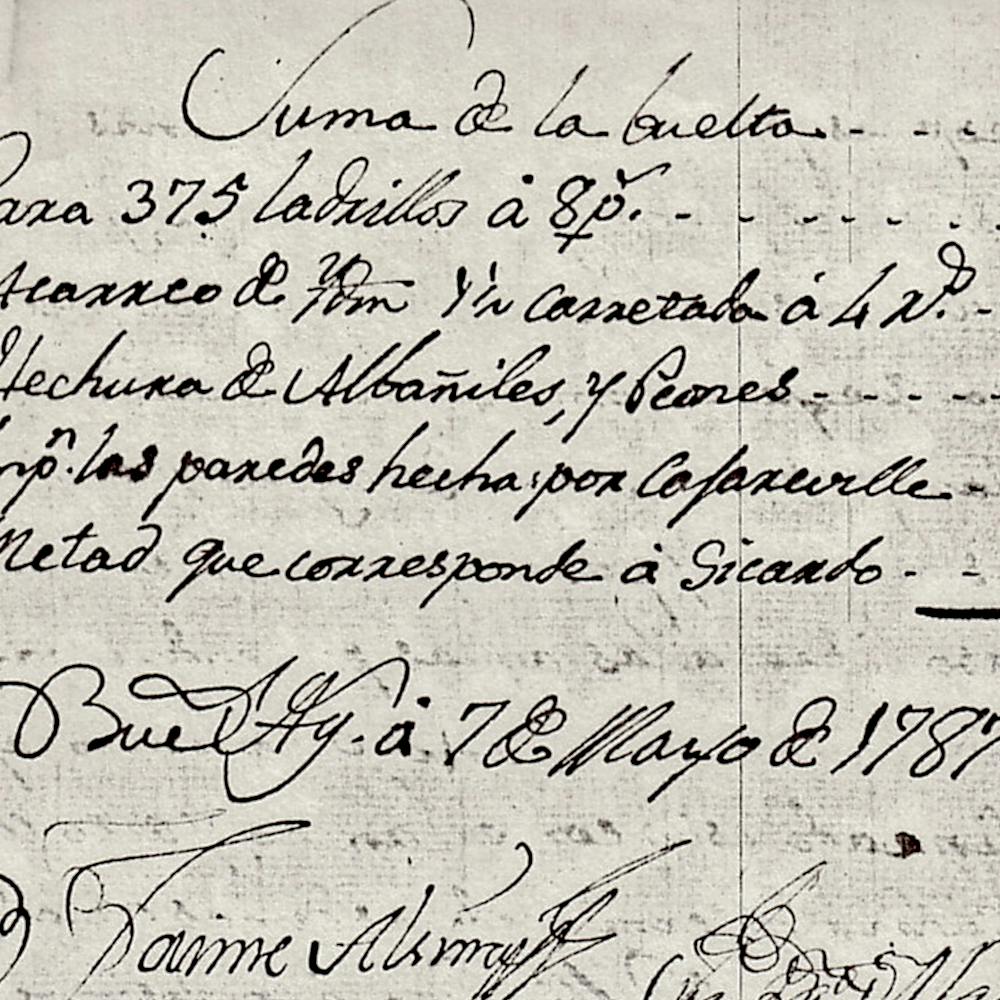

1787

Andres Cajaraville (Marcos Miguens’ son in law) built the first square conduct in the block to contain the violent streams that caused severe flooding during the rainy season, transforming the open sewage system that was designed to reroute this rainwater.

1810s

Buenos Aires severs ties to Spain. Miguel Cajaraville (Marcos Miguens’ grandson) becomes a hero in the Argentine War of Independence.

1830s

The residential mansion of Los Patios is constructed.

1860

The mansion is occupied by Vicente Moujan and Juliana Cajaraville and remained in the family until 1910. During family legal troubles, it is revealed that six slaves are living in the house.

1880-1984

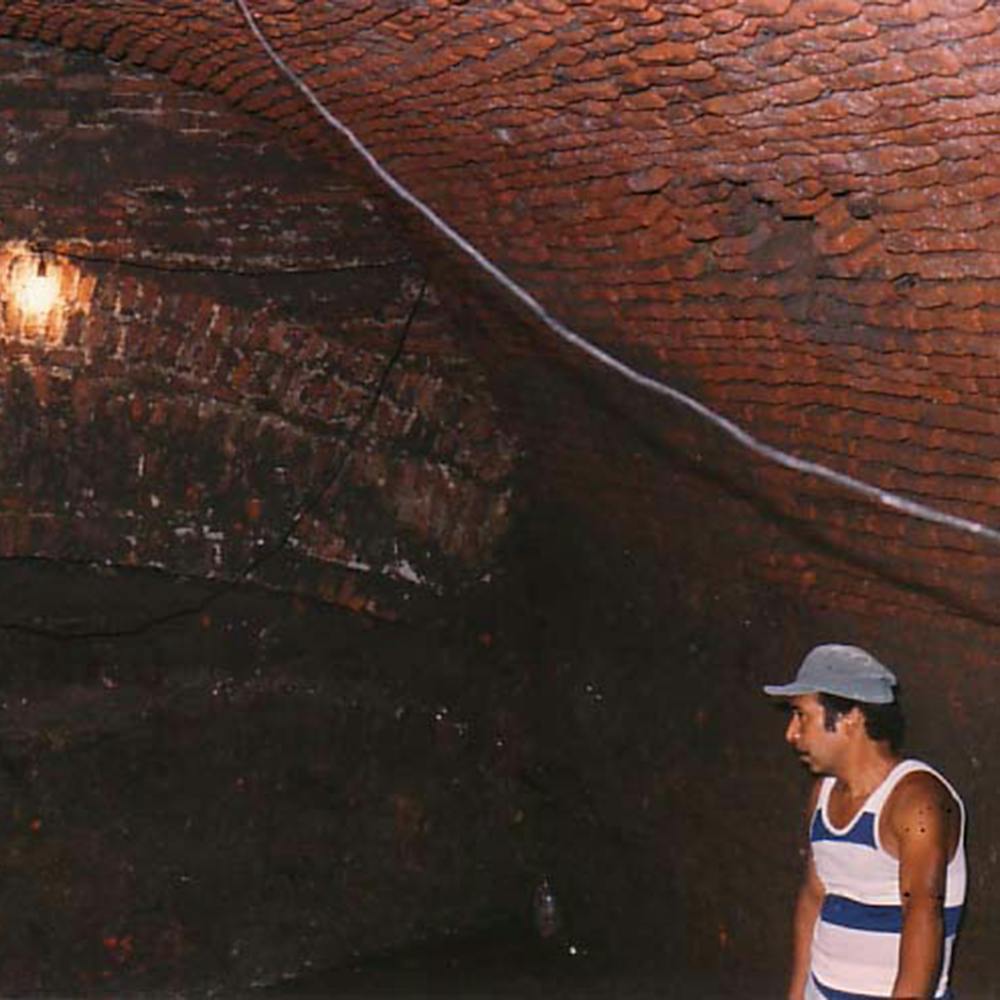

The majestic Los Patios falls on hard times. With industrialization revolutionizing the world, wealthy residents of San Telmo fled to Barrio Norte to escape the yellow fever. Their grand homes became tenement housing for new immigrants, with some 1770 tenement houses in Buenos Aires at this time. Eventually, Los Patios was left to decay, its spectacular tunnels, forgotten.

1880s

The mansion becomes tenement housing consisting of 23 bedrooms and just two bathrooms.

1892

The dramatic death of El Zanjón. The city’s modern sewage system is installed and the tunnels of El Zanjón are filled in.

1940s

Residents of the tenement during this era return to El Zanjón some 60 years later when the site is completed, sharing gossip and intrigue for future visitors.

1970s

The once dignified mansion is abandoned, becoming a local dumping ground.

1985

Jorge Eckstein sees major economic potential in a dilapidated area of his birthplace. Little does the chemical engineer know that his initial investment in land would lead him to a lifetime of conservatorship and the creation of a new method of applying conciliation. The result is the city’s most important archaeological site.

1986

Jorge Eckstein purchases the derelict building of Los Patios and discovers the first tunnel below. This marks the beginning of the El Zanjón restoration project nearly 100 years after the mansion fell from grace.

1994

Jorge Eckstein acquires Casa Mínima, and integrates it into the El Zanjon museum complex.

1996

Jorge Eckstein acquires El Puente — at that time, a paddle court, in order to integrate it into the El Zanjon museum complex.

2001

Los Patios is restored and opens to the public after more than 15 years of painstaking restoration.

2003

Casa Mínima is restored and opens to the public.

2006

With the restoration of El Puente, the museum complex is finally complete nearly 500 years after the founding of the city.

2020

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the final versions of books El Zanjón en Tinta China and Casa Mínima en Tinita China were completed, and the first series of evocative illustrated prints was created.

When Jorge purchased land in San Telmo, the neighbourhood where he grew up, in the early 1980s, he had no idea what mysteries lay below.

With the original intention of a simple property investment where he saw incredible potential (at that point, the residence had been abandoned and walled off, with its ground floor four meters deep in debris), he set about making much needed renovations only to discover one year in that the building he’d bought was in fact resting above a gateway to the origins of Buenos Aires.

This serendipitous occasion led to the accidental birthplace of an idea, and the personal emotions that followed generated even more discoveries of understanding and connections—between himself, his friends, his neighbors, the building’s past and the history of the city.

Jorge spent 38 years relentlessly advocating for El Zanjón, devoting his time, energy and resources to research and bringing this historical monument to the world. His relentless quest for perfection was fueled by his devotion, passion and conviction, and the result is a singular object of architecture full of love, care and dedication.

Through the joy of discovery, the joy of creating and the joy of giving, Jorge has found a new way of being.

That is El Zanjón.

“I became Argentinian the day I began this project. That day I started working for myself and for the country with equal intensity, the same way I conciliated a cultural project with a commercial one and neither one imposed itself over the other.”

Jorge Eckstein